The Gruesome Tale of Winter’s Gibbet

On a rainy night in 1791, an elderly woman by the name of Margaret Crozier answers the door to a sodden man seeking shelter. Allowing this stranger into her home began not only the end of Margaret Crozier’s life, but the unnerving story of a gibbet that has become entwined in Northumbrian ghost lore.

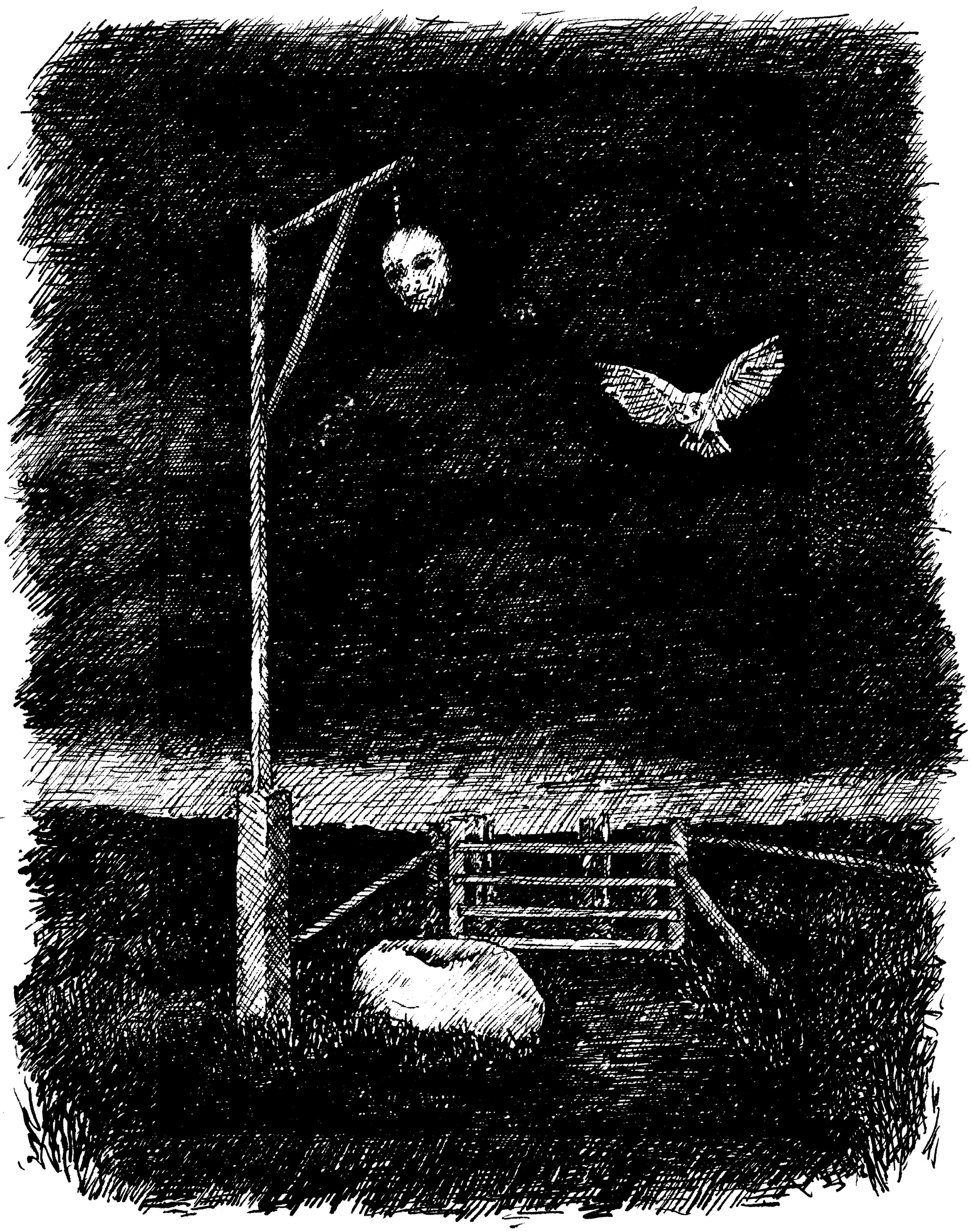

A stone’s throw from the village of Elsdon, in the midst of bleak Northumbrian moorland, stands a lone gallows. From it, a wooden macabre head swings spookily in the wind. This eerie executioner’s pole is known as Winter’s Gibbet, and it serves as a stark reminder of a grisly murder that took place here in 1791. The victim was an elderly woman by the name of Margaret Crozier. She lived at Raw Pele, within a small hamlet two miles south of Elsdon. For a living, Margaret kept a small shop, selling drapery and other goods to the local community and travellers making their way along the nearby drover’s road.

One miserable Monday evening on the 29th of August 1791, two of Margaret’s friends, Elizabeth Jackson and Mary Temple, arrived at Raw Pele to spend the evening in her company. A few hours later, as the women prepared to leave, they were startled by the sound of a dog barking furiously in the direction of a pile of hay lying close to Margaret’s house. Unsettled by the commotion outside, as the two women left, they reminded Margaret to bolt her door.

Early the next morning one of Margaret’s customers, Barbara Drummond, arrived at the shop to make a purchase. As she approached the entrance to Raw Pele, she noticed something untoward - thread and other small items from the shop lay discarded outside of the shop doorway. Suspecting something was amiss, she hurried to alert Margaret’s neighbours. Having not seen Margaret that morning, Elizabeth Jackson and her husband William Dodds expressing grave concern rushed to the shop and opened the door. A dreadful sight awaited the couple. They found the old woman lying lifeless on her bed, her throat cut and bound up tightly with a handkerchief. Beside her lay a long blood-stained gully knife, the type typically used by a butcher. The palm of one of her hands was severely lacerated, suggesting Margaret had fought desperately for her life. It soon became apparent that various articles of clothing, materials and linen had been stolen from her shop.

Unsurprisingly, local people were horrified to learn that such a gruesome crime had been committed in such a remote and isolated community. Before long, many people regardless of class or position became actively involved in the hunt for the killer. A reward was offered for any information that may lead to an arrest and the authorities pleaded with local people to report any strangers or unusual behaviour they may have witnessed in the run-up to the murder. Two young boys came forward who had seen a man and two women acting suspiciously the day before the killing. The three suspects had been resting and dining at a sheepfold on Whisker-Shield Common overlooking Raw Peel. The boys described the man as six feet tall, of a powerful build with tied back long black hair. He wore a light-coloured coat and blue breeches with grey stockings. The two women were also described as tall and dressed in grey cloaks and black bonnets. One of the boys, Richard Hindmarsh, paid particular attention to a large gully knife in the possession of the male suspect. He had used the knife to divide food amongst the trio. As the man sat enjoying his meal, Hindmarsh had also been able to observe his feet, noting the specific type and quantity of nails in the bottom of his shoes.

The new evidence was quickly reported to the coroner who delayed the inquest until the witnesses could appear. Being the more observant of the two, the young Richard Hindmarsh relayed his observations. Upon being shown the knife found at the scene of the murder, he identified it as the same one used by the man to divide food amongst the group. Distinctive footmarks found outside the house at Raw also corresponded to Hindmarsh’s description.

Following this breakthrough, other local people who had seen the strangers then came forward with information. It was discovered that the suspects had later been spotted with a loaded mule near Harlow Hill. Following the clues, local constables eventually found and arrested a man by the name of William Winter near the village of Horsley. The two women, sisters Jane and Eleanor Clark, were apprehended sometime later at Ovingham and Barley Moor respectively. All were found to be connected to the ‘Faw Gangs’ which were tribes of gypsies prevalent in Northumbria at this time. The suspects were taken to Mitford to be examined. Winter’s shirt was found to be stained with blood, which he alleged happened while fighting with another of his tribe. These claims were quickly discarded as it was pointed out that Winter would most likely have removed his shirt if involved in such a fight. The evidence was stacked against them and the three were committed to Morpeth Gaol on September 3rd 1791.

The courts at this time were held once a year, as such the trio remained in gaol until the following August when their trial was held at the Moot Hall in Newcastle. It lasted sixteen hours and the two young boys brought forward their evidence concerning the knife and footprints. A close friend of Margaret Crozier also identified a nightcap found in possession of one of the accused females, as being one she had made herself for the murdered woman. The three prisoners were subsequently found guilty and sentenced to death. The sentence ordered that William Winter’s body was to be hung in chains on a gibbet within sight of the scene of the murder - a punishment reminiscent of the gibbeting of Border Reivers when corpses were left hanging as a warning to others. The bodies of the two female accomplices would be sent to physicians for dissection.

On Friday morning, 10th of August 1792, all three were hanged at Westgate, Newcastle upon Tyne. Prior to the execution William Winter admitted his guilt, although the two sisters continued to protest their innocence until the very end. Winter’s body was left to hang on the gallows before being cut down and transported by cart to its final exposure on a gibbet at Steng Cross. Thousands of people gathered to watch as the body was hoisted into position. Winter’s corpse was left to hang from the gibbet until his clothes rotted off.

In the beginning, the deathly smell emanating from the remains was so offensive that even horses refused to pass by. Once decomposed, Winter’s loose bones were collected and hung in a sack, tarred from the inside to resist the harsh weather of the exposed moors. Over time, this too decayed and the fallen remains were buried by local shepherds. When the last of William Winter had disappeared, a wooden figure of a man was hung from the gibbet, but this too eventually succumbed to the ravages of time and exposure to the elements. Local people who believed that splinters of wood from the gibbet cured toothache, precipitated its destruction. The gibbet has since been remade several times since the original stood. No matter how many times the executioner’s pole has been stolen, vandalised, or destroyed by the weather, it is always rebuilt. Today the local custom is to hang a stone or fibreglass head from the noose, although this too tends to disappear regularly…

Although the murder of Margaret Crozier took place over two hundred years ago and William Winter’s body has long since disappeared, the lasting reminder of Winter’s gibbet continues to be regarded with a hint of suspicion and horror.

Illustration by Rachel Edwards